Introduction

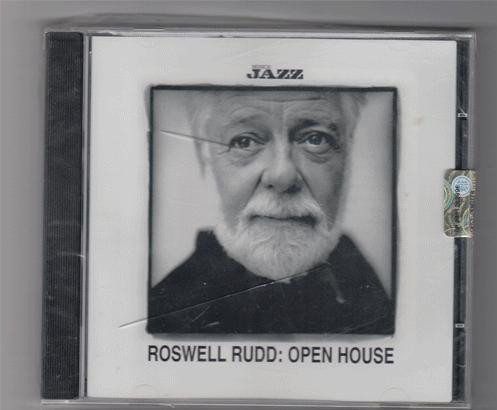

Trombonist Roswell Rudd was one of the great spirits to have taken part in Jazz’s development through the late 20th century. We often say of mercurial, multifaceted performers that they "reinvent themselves" into various personae. It may be truer for Rudd that he had invented already by 1963 a self he would stay with while the world found new ways to situate his talent, as he dodged in and out of view from one period to another. Describing what seemed from the outside to be a re-emergence, he coyly remarked, "I never left, and now I'm back!"

Rudd was an impressive and very personal voice on the trombone; he would say he was in fact channeling the thrust and character of trombonists from an earlier time—maybe even tracing all the way back to the prehistoric depths of human (does it even go back farther?) music-making. Along his journey, he joined as a young man what already was the oldest contingent of Jazz players, then shortly fell into step with the most progressive. For the rest of his life Roswell was a standard-bearer for the principle that meaningful, lively musical expression is the bedrock of Jazz, whatever ‘style’ it belongs to.

Chapter 1

Roswell Rudd’s family came from Lakeville, Connecticut. He was born in nearby Sharon, November 17, 1935, the second child of Josephine and Roswell Hopkins Rudd, Sr. who already had an older girl and would have one more; both of Roswell’s sisters survived him into 2018.

Roswell was indoctrinated into music through the very local sources emphasized by his family musical surroundings, and by contemplating the masters at close range. Both parents were involved in education in New England, so the family moved where their work took them—west into New York State near Ithaca, and east to the Hotchkiss School in Salisbury, Connecticut. Roswell’s father, the still legendary ‘Hop’ Rudd, was the guru of recreation and recreational music at these several schools; he was a drummer and jazz enthusiast whose gusto rubbed off directly on his son. Roswell was trained on French horn, trombone and mellophone from his elementary school years.

While in school he witnessed several Jazz performances that propelled his career and endured in his memory. One was by a group of old masters in a Dixieland concert performance at Hamilton College—including New Orleans veteran bassist Pops Foster and stride piano forefather James P. Johnson. By age 11 Roswell was hooked. In the early Fifties he attended a Jazz at the Philharmonic concert with a friend in New York, and was further galvanized. His listening pattern focused on the talents of Woody Herman’s trombone star Bill Harris and swing veteran Vic Dickenson, and young Roz (as he then signed his name) latched onto retro jam session records like Jammin at Rudi’s #2, memorizing every note.

Roswell rode the wave of a 1950s renewal of interest in the polyphony of early Jazz. When he started school at Yale in the fall of 1954, he joined a combo of Yale students called Eli’s Chosen Six, referring to founder Eli Yale. (Thanks to Marshall Stearns, George Avakian, and others, Yale had an uncommonly high profile in Jazz at the time.) Hop Rudd’s son was still new in the band at a point when the father appeared as a sort of emeritus guest star on drums in the recording of Eli’s Chosen Six that gives us the first recorded glimpse of Roz. The second one was not far behind: Though the band predictably played campus functions and local spots, they also parlayed the Yale connection into a 1955 record on Columbia, followed by another LP (both featuring Roswell) in 1957. The band was featured prominently in a 1958 film, though without Rudd. That summer he was playing music on a trans-Atlantic cruise ship, so his screen debut would wait another few minutes.

Through the end of the Fifties, he mostly played on a circuit of here-and-there work in the Dixieland field—based out of Connecticut, looping to New York when possible, and making long jumps to work a substitute week with some of his heroes. So far, every part of Roswell’s ambition and practice in the field of music related to traditional Jazz of one sort or another.

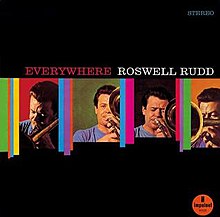

Bill Harris and the Ex-Hermanites - Everywhere

Chapter 2

By 1960, Roswell Rudd was officially through with formal school education. He moved from New England to Jazz’s capital city, New York, where he enrolled at once in several finishing schools, effectively, for himself as a working Jazz musician.

He rented an apartment in an ancient unheated dwelling at 128 Broad Street and started a job at the customs house—affordable and flexible enough (respectively) to let him play music in the area and make occasional road ventures, like the one as to Chicago with an Eddie Condon group. What was the music? Still mostly Dixieland. He even got called to appear with a pick-up band visible on screen in the major motion picture The Hustler.

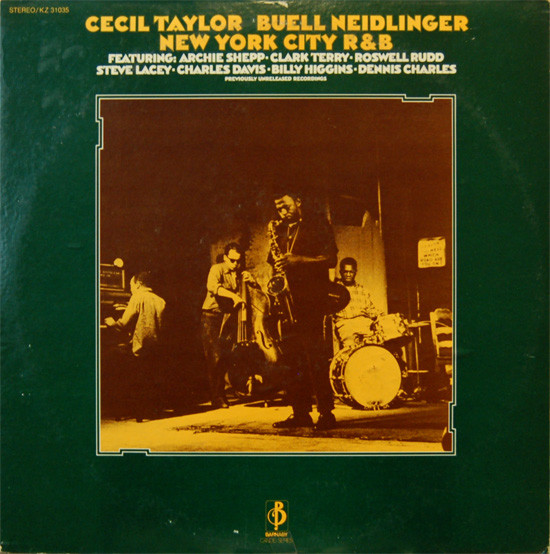

While still in Connecticut, Rudd had made two significant connections that would continue to be important to him in New York—both with players of his generation who, like Roswell, were captivated by the Jazz from two generations before theirs. Bassist Buell Neidlinger (1936–2018) was one, and the other reedman Steve Lacy (1934–2004), who was just then leaving behind the clarinet to focus full time on soprano saxophone. Both were precocious journeyman players, and they had a hand in the overlooked Fifties sub-movement known as “progressive Dixieland”. Perhaps most importantly for Roswell, both were increasingly wrapped up with the extreme edge of Jazz modernity, via pianist/composers Thelonious Monk, Herbie Nichols, and Cecil Taylor.

This alloy of forces in Rudd’s 1960–61 set the pace for the rest of his career: He studied the essence of musical design via Monk and Nichols (and arranging through Ellington and Strayhorn), while forever chasing the nuanced perfection of that collectively improvised Dixieland last chorus—even into the wide open spaces predicted by the new Free Jazz subgenre.

-

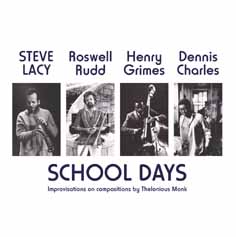

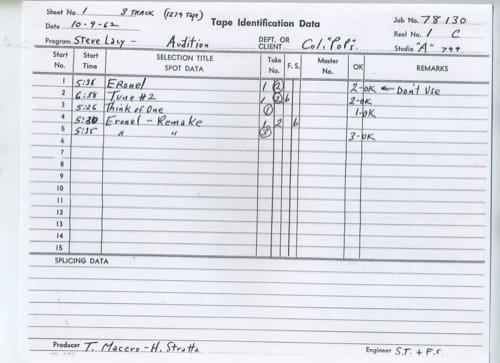

Thelonious Monk (1917–82): Most modern Jazz musicians in 1960 freely acknowledged Thelonious Monk as the High Priest of everything that had happened since Bebop. No one took that reverence farther than Roswell and Steve Lacy, who founded a quartet in 1961 devoted entirely to pianoless, two-horn versions of Monk’s compositions. They were ready to perform any published Monk composition, and for some sections of the quartet’s three-year history they played only his music.

-

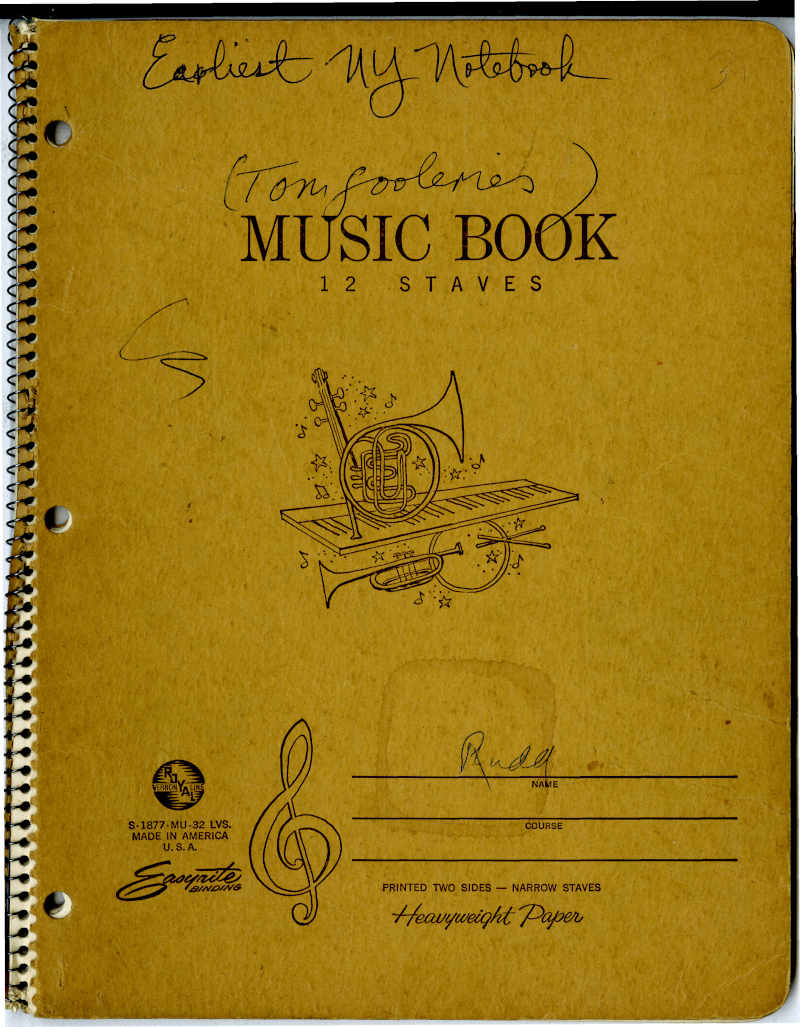

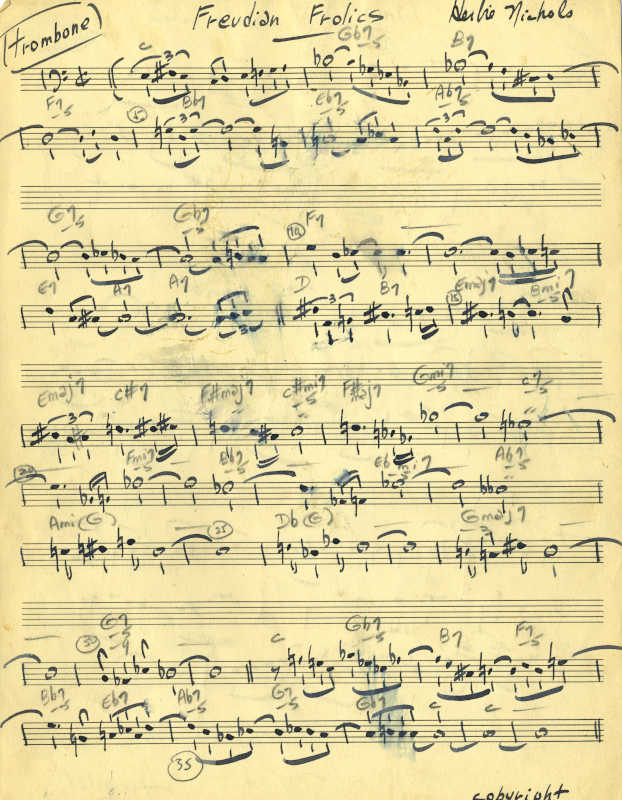

Herbie Nichols (1919–63): Rudd was the last great pupil (Was he also the first?) of Herbie Nichols’s offbeat genius as a composer. Roswell apprenticed with the master craftsman, learning through Nichols’s written compositions not the regular flow of pop and Jazz songs, but Herbie Nichols’s unpredictable melodic shapes and harmonic motion. Those lessons were profound for the young trombonist; through to his own dying day, he treasured and kept with him both the insight and written music that he had absorbed from Herbie Nichols through the last two years of Nichols’s short life.

-

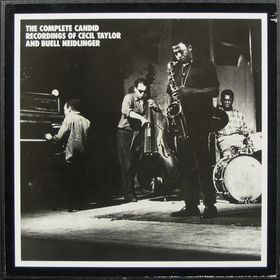

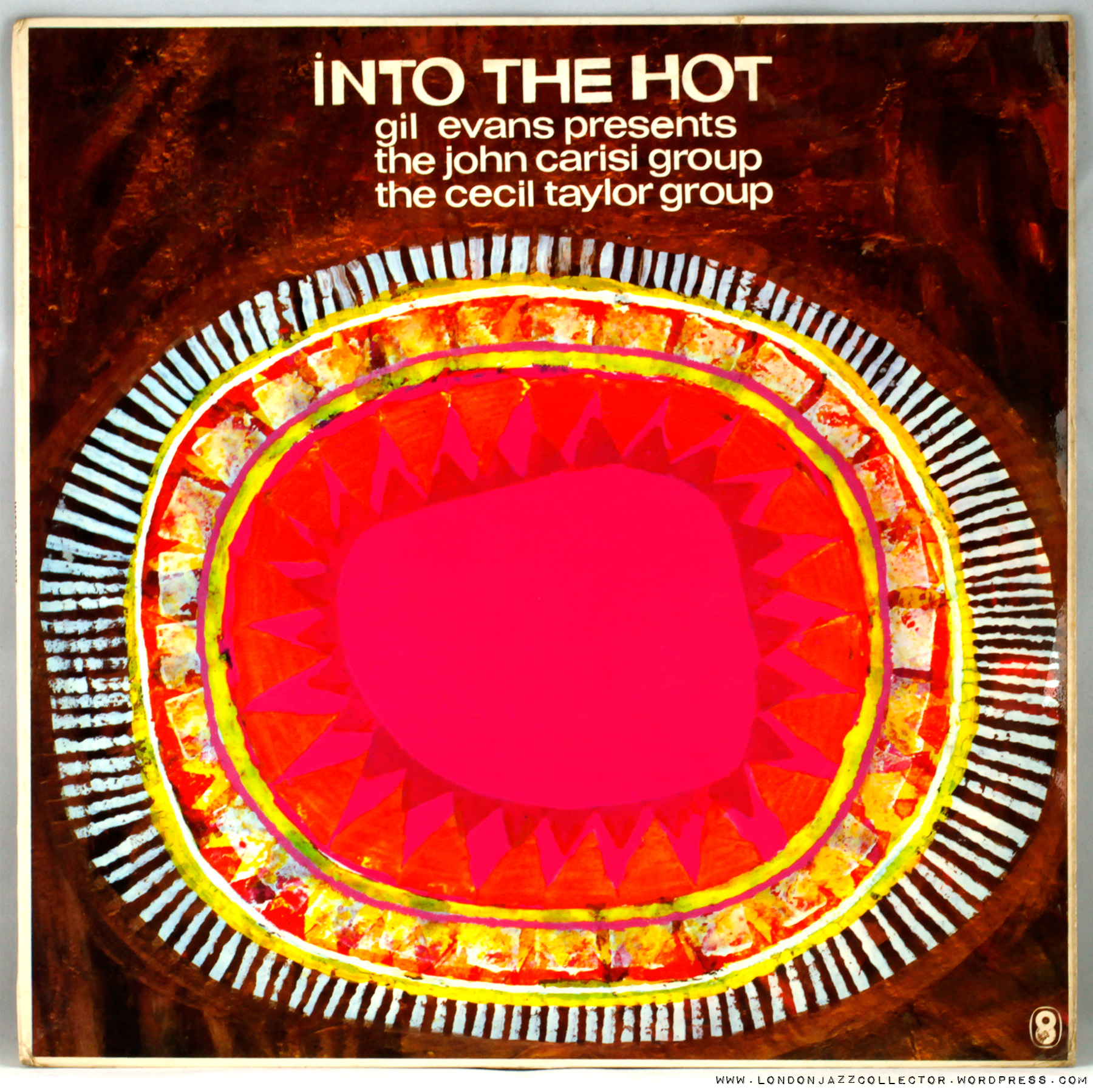

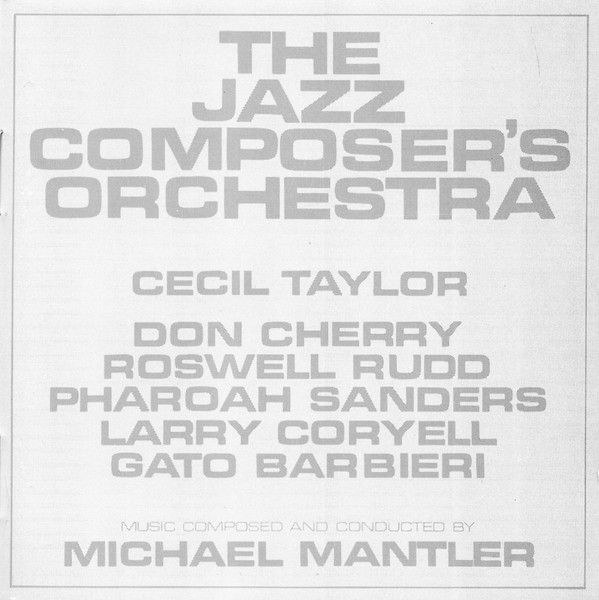

Cecil Taylor (1929–2018): The next two record dates for Rudd were in the company of the enigmatic Cecil Taylor: First on Buell Neidlinger’s January 10, 1961 project, for which Roswell derived eight-part arrangements of two tunes from the Ellington world. Later he was added as the fourth wind voice on one track (“Mixed”) of a Taylor project sponsored by Gil Evans. As one of his contemporaries put it: Rudd played these two glissandi in the opening phrases, some off-mic duet passages opposite Jimmy Lyons… and the next thing you know, Roswell Rudd’s name is on everyone’s lips.

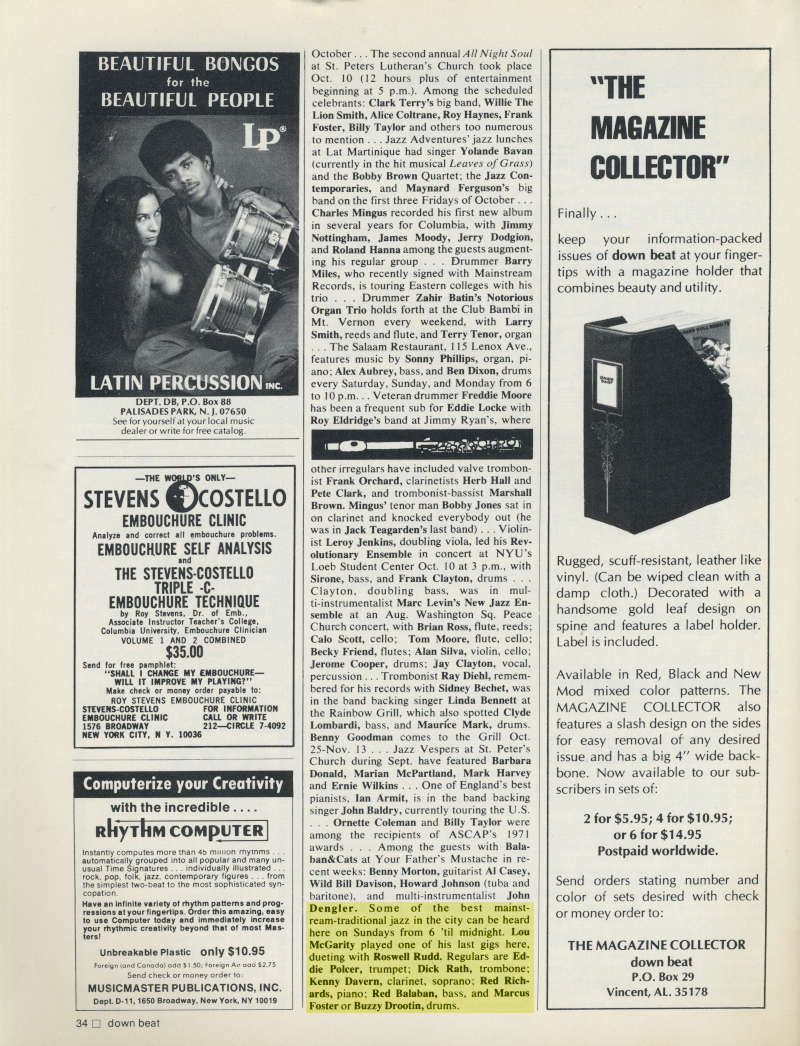

Rudd was by no means enjoying the life of a star or even a Jazz star, and arguably none of the above amounted to sustainable exposure, but he did win 1963’s New Star award from down beat magazine in the trombone category. The more enlightened press notices from the period commented specifically on Rudd as one great young player with a new muscular, maybe even "brutalist" expression on trombone— putting the ‘gutter’ back in "guttural"—as part of a counterstatement to the sophistry and agility of Bebop stylists on the instrument.

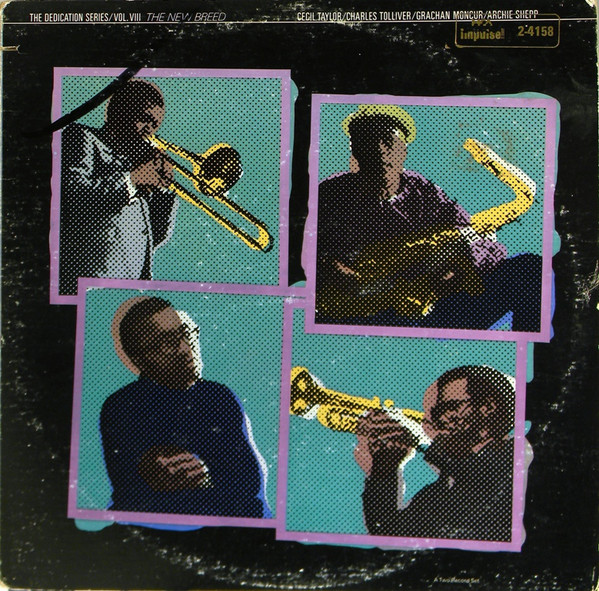

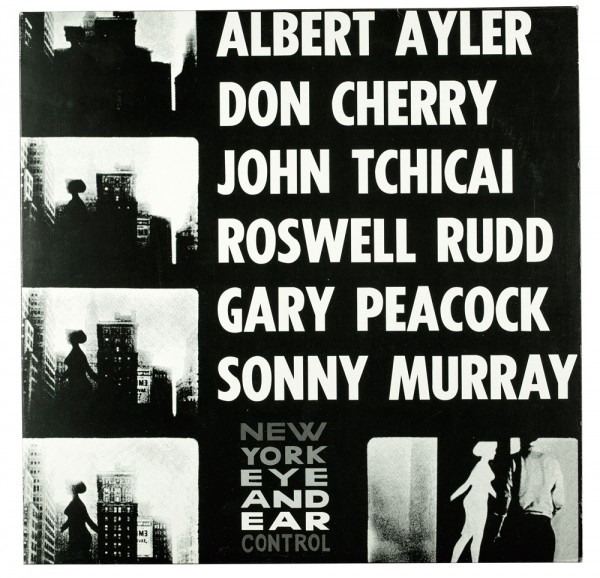

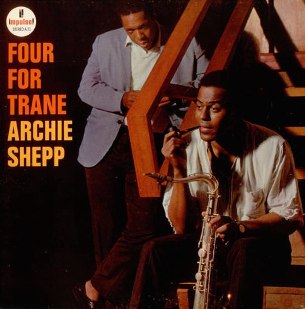

By the end of the Lacy–Rudd band that played other composers’ modern Jazz classics, the co-leaders were ready to spend more time developing their own music, which would be a definer in Rudd’s next frame. He was increasingly part of the musical ferment of the second wave of New York Free Jazz, especially defined by the players in the circle of Cecil Taylor. Roswell was the favored trombone voice in the leader career of tenor saxophonist Archie Shepp, and called on to arrange Coltrane’s music for Shepp’s masterpiece Four For Trane in 1964.

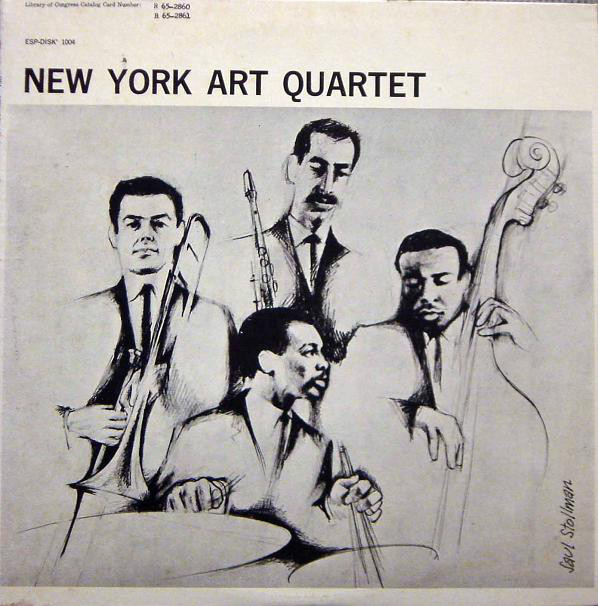

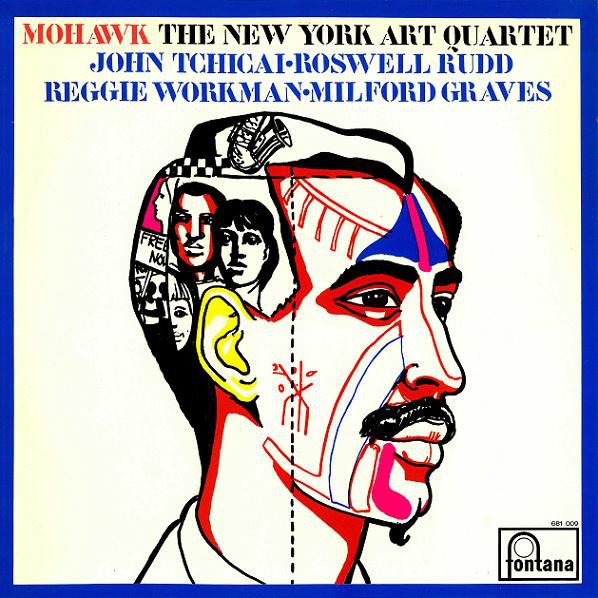

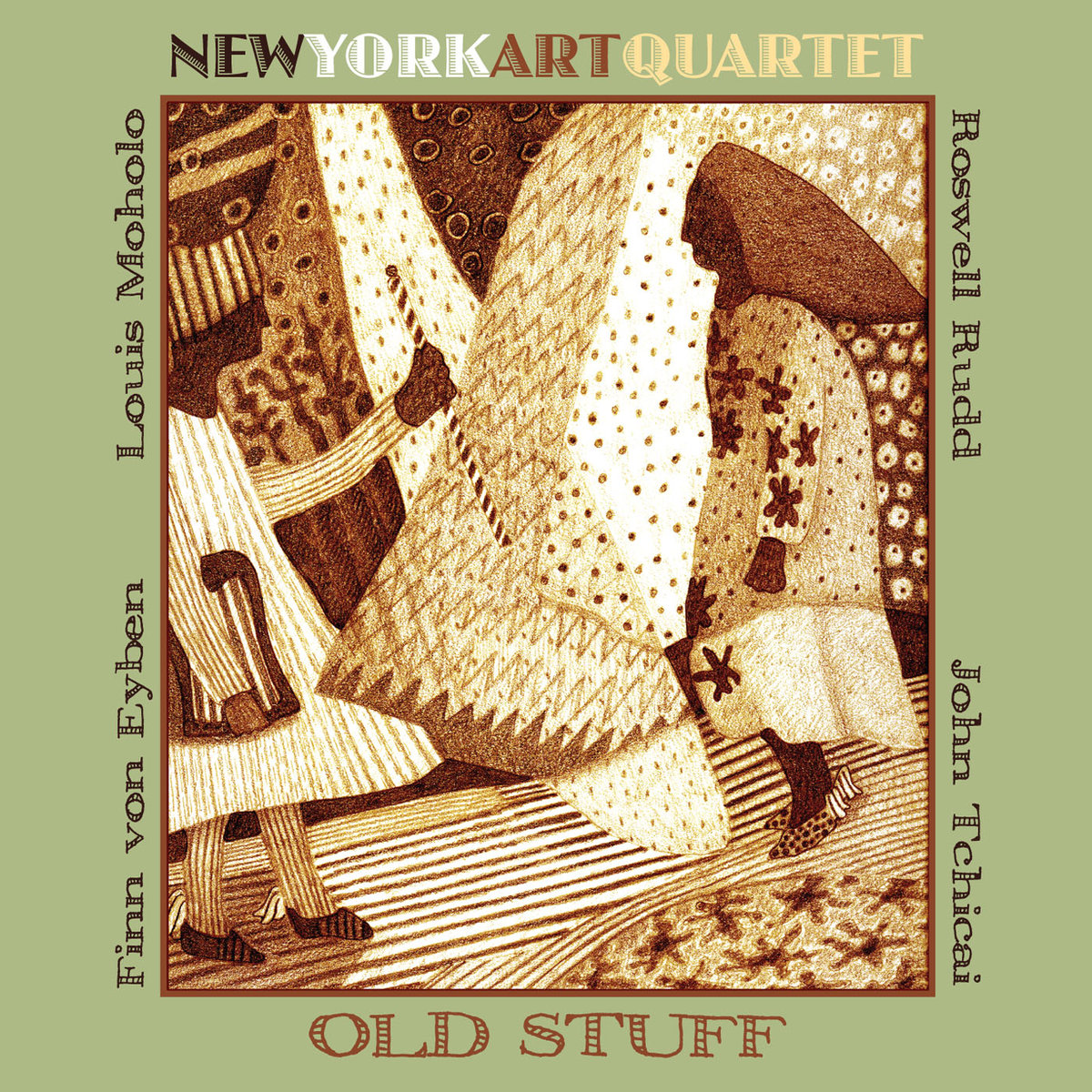

Through this bracket of associations, Rudd also found a vital collaborator in the Danish-born alto saxophonist John Tchicai (1936–2012). They co-founded in 1964 the New York Art Quartet, whose fluid delivery of the breakthroughs of modern Free Jazz was as potent and impressive as any group on the scene. Alongside Tchicai and Archie Shepp, Roswell was a charter member of the Jazz Composers Guild, a collective- bargaining professional organization founded in 1964 by Bill Dixon. The Guild became the principal framework for exposing the New York Art Quartet, and the NYAQ itself was the first way we would hear Roswell’s ideas as composer—syncretized through so many years of jotting and transcribing and recasting the work of others, now grown into his own individual voice.

Chapter 3

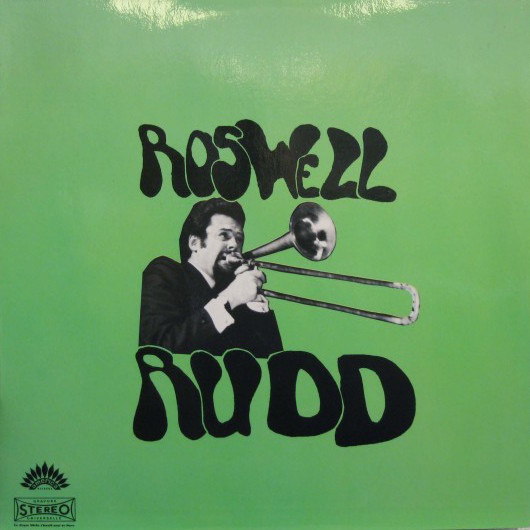

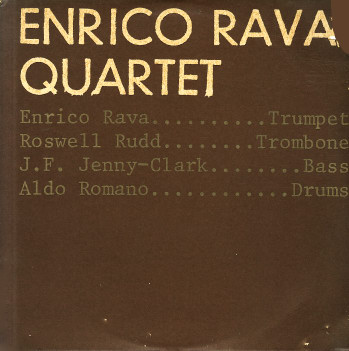

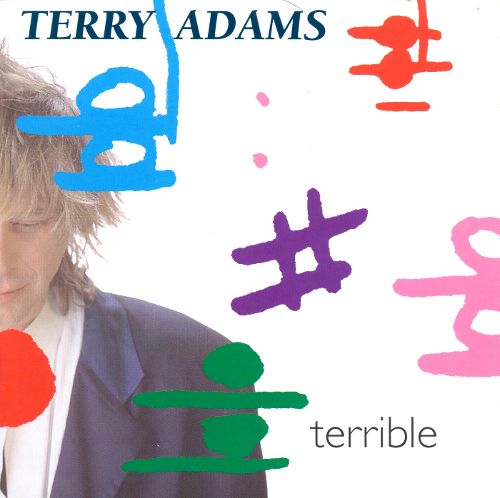

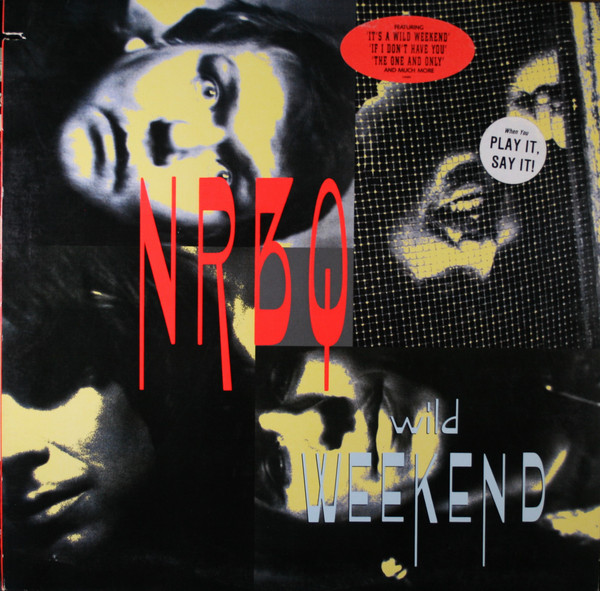

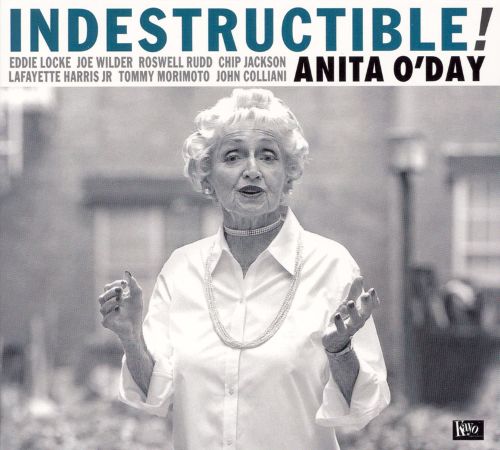

The New York Art Quartet planned to perform into 1966 but fell short by several months, finding a stronger pull toward their own individual projects. The next plateau for Roswell is represented by one album for Impulse, from one day’s studio work in July of 1966. With a two-bass, two-reed sextet he paid respects to his inspirations Bill Harris and Herbie Nichols, reedman Giuseppi Logan who appeared on the session, and included an updating of one of his three-year-old originals. This was Roswell Rudd’s first recording session as leader, made when he was 30.

Though Roswell himself wasn’t one to speak in such terms, we might observe that this LP Everywhere didn’t really lead anywhere. It was his latest of several appearances on Impulse—first as an add-on for one track with Cecil Taylor, then as arranger and supporting cast member with Archie Shepp in studio in 1964, and as a regular road sideman for Shepp before and after Everywhere. But afterward the flow of opportunity dried up quickly. The record business had afforded Roswell Rudd a tryout but apparently didn’t see sufficient promise to go further. Seven years later his next appearance leading a record grew out of the DIY spirit of the Jazz Composers Orchestra (Association).

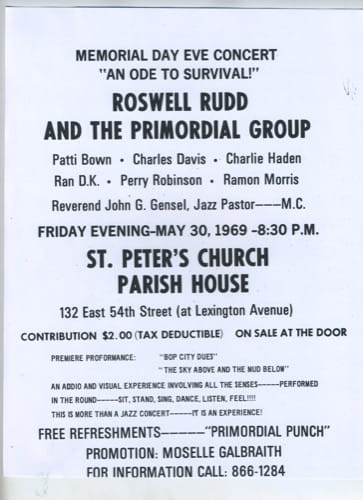

Roswell shared with the JCO/A a tenacious, self-sufficient spirit—maybe it’s actually "defiance"?—and bore down emphatically on writing, performing and recording independently music that went unheralded and in some cases remains undocumented. As early as 1965, Rudd had been writing suites and connected long-form works, with characters, plot, and words. Hometown Suite is probably the first we can point to, then the opera The Gold Rush that got its fullest treatment in recordings from spring 1967. His Blues for Planet Earth had two concert performances in New York, one of which was recorded in full, as was Springsong also from 1968.

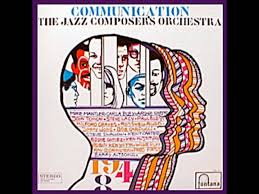

Through the late 1960s, Rudd continued to perform with others—Shepp through 1967, Robin Kenyatta in 1968. He had been a charter member of the Jazz Composer’s Orchestra since the Guild days, and was one of the featured soloists within Michael Mantler’s Communications cycle in 1968. He plays the first notes of Carla Bley’s JCOA masterwork, Escalator Over The Hill. Eventually it was Roswell’s turn to write for the ensemble, generating a five-part suite called Numatik Swing Band. It was workshopped by the JCOA in 1971, and then revived two years later, recorded and released. Numatik Swing Band stands as the most involved single work of composition in Roswell Rudd’s catalog. It crowned this middle period of orchestral development, and arguably is his masterpiece as orchestrator and composer. Numatik also turns out to be the swansong of this phase of his career, and of 13 years of living in the city.

Along the way Roswell Rudd became a family man: In 1963 he and photographer/artist Marilyn Schwartz had gotten married. With the birth of their son, Greg, there was now parenting to factor into their lifestyles.

Though he prized and was prized by a musical discipline celebrating improvisation, Roswell was always a writer of music and student of the written word. Take a look at the manuscripts in this site’s galleries to appreciate that Rudd used the full breadth of music notation to generate the precise nuances he sought in his pieces. Beginning in the mid-Sixties, Roswell wedded this skill of documentation with an interest and aptitude in non-western folk music systems, when he took work with the pioneering ethnomusicologist Alan Lomax. Rudd’s involvement came at the beginning of Lomax’s cantometrics, a system of coordinating musical and social characteristics of the world’s cultures. Roswell’s work with this initiative would continue in the background off and on until the project concluded in 1994.

Chapter 4

Rudd’s 1970s profile probably had more moving parts to it than any other segment of his life, and the day-to-day reality might not be perfectly reflected in the seeming continuity of strong records from the period.

His first marriage wouldn’t last out of the 1960s; in the time of Numatik Swing Band Roswell began a new family with Moselle Galbraith Rudd. They married in 1970, had a son together, Chris, and brought now three children from previous marriages into a complex family life based in New York City and eventually upstate.

Rudd also added a new career direction when he became a lecturer at Bard College in 1972 in Jazz performance and history, and world musical cultures. For this work he could still be based in New York City, teach in a Brooklyn high school, and commute once a week up to the work at Bard… and also drive a cab in between to help ends meet. Once Roswell took an appointment in 1976 at the University of Maine, he transplanted the family to Augusta and lived again in New England for the first time since the Fifties.

Roswell’s career and outlook as an educator are among the least chronicled of his professional dimensions—and surely a matter for further study within and beyond the Jazz History Database. On the one hand, he was good at teaching: He comfortably grasped all the mechanics and aesthetics of centuries of music production. And he was passionately invested in passing it on—plus he had the patience and demeanor to engage students who were at all levels. On the other hand, Rudd as a musical omnivore was no doubt challenged to meet the need of compartmentalizing for formal teaching… on top of the persistent challenge for musicians who are actively playing and teaching: How can you commit to both?

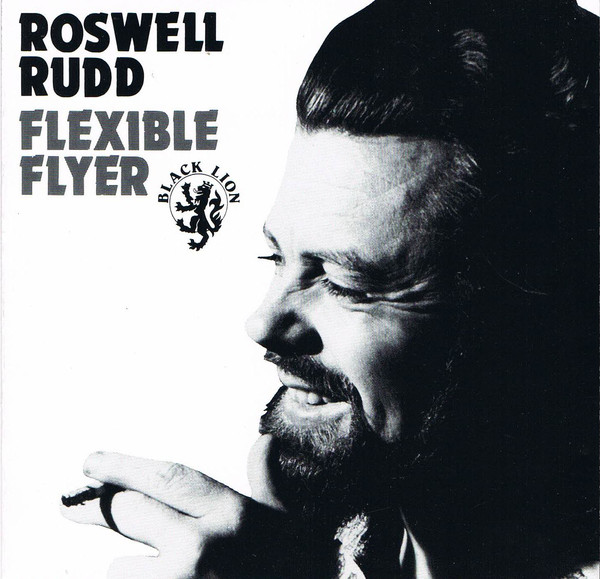

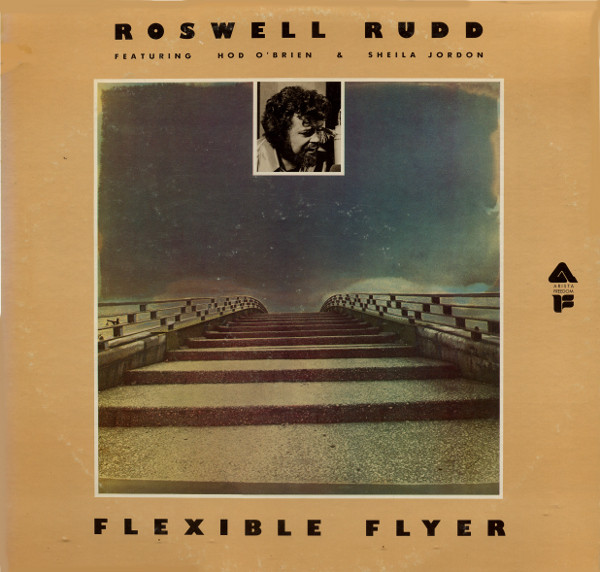

Many of Roswell’s contemporaries worked during the Seventies in musician-owned and operated, independent, informal presentation spaces, what we refer to as the "Lofts" of lower Manhattan. Roswell is largely absent from narratives about the Lofts, and in fact he was not greatly present on that scene. Rudd’s friend from grade school, pianist Hod O’Brien, had opened a Chelsea basement as the St. James Infirmary, in order to have a place that he could stay limber as a performer. He engaged Moselle as the musical director there, which led to frequent appearances for Rudd of bands that drew on some of the same talent as the records Flexible Flyer, Inside Job, and Blown Bone.

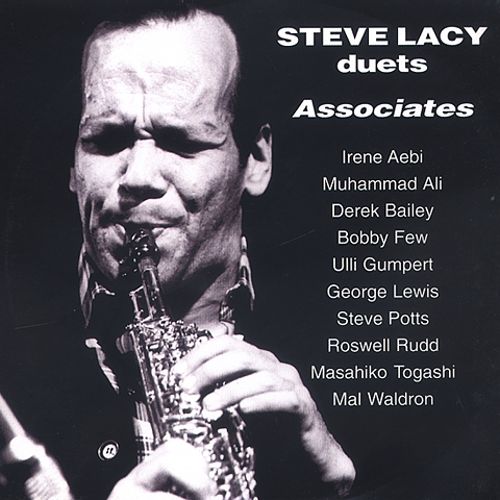

While teaching further solidified Roswell’s pedagogical materials, he of course continued to write music. Some pieces that we now see as Roswell Rudd standards showed up in the period on his two records for Arista—and some didn’t. Though it’s easily overlooked, the aforementioned Blown Bone (recorded in New York, but only released on LP in Japan) was another cornerstone album that Rudd took great pride in. In 1976 Rudd and Steve Lacy exchanged appearances on each other’s records and toured to Canada as a duo, but these pockets of activity can mislead us into perceiving greater continuity to their association than there actually was. Lacy still lived in Europe full time, and Roswell was about to live full time in Maine.

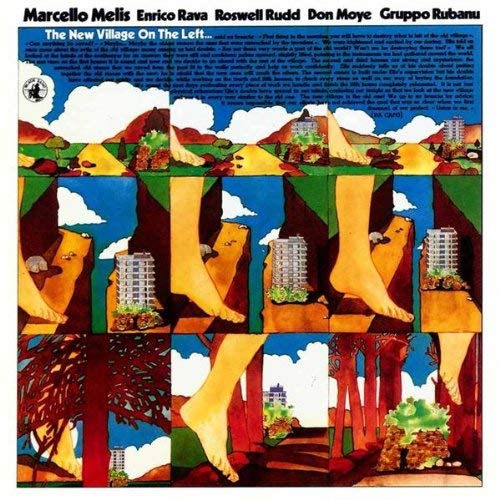

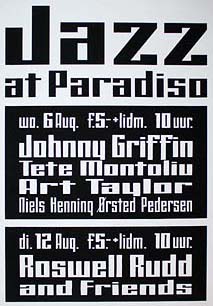

"The Message from Maine" was one Rudd piece that typified the era; he in fact performed it in person during trips to Holland, Italy and Germany while living in Maine the rest of the time. As was true of the music at large, there was as much or more opportunity for work in Europe than in his home country, and we started to hear Roswell’s musical message regularly ricocheted back to the US via import records on ECM, Horo, BVHaast, Black Saint—a pattern of activity that continued through the rest of his life.

Chapter 5

The 1980s were surely the least visible period of Roswell’s career—an even more disparate scope of activity matched with seemingly desperate living—at least as it appeared to outsiders. Roswell’s home base for much of the Eighties was in Ulster County, New York, where he was responsible for the needs of his largely homebound spouse Moselle, school-age children and beloved pets. The strong pull of this responsibility meant that work needed to be local. Teaching was irregular; recording was irregular; the momentum of the loft-era had cooled significantly, and even living and non-music work situations were inconstant.

Along the way, Roswell caught the last sparks of a sector of Hudson Valley entertainment history that had quietly entwined with Jazz for decades: Commercial work in the Catskills resorts. Life in the "Borscht Belt", especially in summer, remains an active reality for many New Yorkers wishing a cooler retreat out of the city. From the 1930s (or earlier) into the Eighties, numerous venues offered live music for dancing and casual entertainment; at some venues there were even organized cabaret-style stage shows.

Roswell joined up with one such performing team, at the Granit Hotel near Kerhonkson, NY. Like Rudd, they were serious players and seriously talented but largely off the grid: Alto saxophonist Ron Finck, Erskine Hawkins trumpet alum Bobby Johnson, tubaist David Winograd, and others. The Granit show blended real jazz content with pop and show novelties. On paper no one might see this an apex of his career, but the activity there drew on most of the skills Roswell had been developing his whole life: Finding the art in entertainment, and executing music well even within pop-digestible vehicles. Roswell credits the Granit experience—especially coping with comedians’ off-script spontaneity—as a spur for the vocal routines that in his music thereafter, spoken and sung. A certain kind of dramatic posture had already been part of Roswell’s writing from The Gold Rush (1966) through "God had a Girlfriend" (1975) and beyond. Through the hotel band experience, that spirit brought a personalized showman’s flair to his performances as well. It was the right gig at the right time, and comprises most of Roswell’s music-making between 1983 and about 1992, when the show was finally dismantled.

Surrounding this continuity were career high points and low points. While Roswell always kindled a sense of the dignity of labor and human interactions, life logistics still demanded menial work outside of music—bread deliveries on the pre-dawn shift, health care work in senior centers. But there was also a steady but slow stream of worldwide recognition that kept him active both in the Hudson Valley and internationally. Among the highlights were meeting some of the players who came up into the Catskills looking for him: Saxophonist Allen Lowe, for an enigmatic American songbook project; saxophonist Charlie Kohlhase, who put together a Roswell Rudd songbook project; and the English saxophonist Elton Dean, who invited Roswell on a fondly-remembered tour overseas. Among other artifacts from the early Nineties were a recording with trombonist Steve Swell that led Roz to record his trio playing Herbie Nichols’s compositions.

Chapter 6

Discussing the final segments of Roswell’s life and career pivots on the multi-talented Verna Gillis, Rudd’s partner and producer for the last two decades of his life. Gillis has a passion for meaningful music in any language or no language. She spent early chapters of her adult life traveling the world, studying and documenting the indigenous musics of Haiti, Surinam, Cuba, the Dominican Republic, West Africa, and North America. Gillis in 1974 launched the WBAI radio program Soundscape, which welded her intense devotion to native musics to the new ferment of avant garde Jazz in the Lofts, and for that matter to the last stages of pre-digital artful vernacular pop music. Gillis in 1978 opened a 52nd Street performance venue also called Soundscape, where a steady schedule mirrored the same content—mostly jazz-based improvised music, but inclusive of new international avant garde performers, and a weekly Latin Jazz jam session that became a primary US foothold for rising star musicians recently immigrated from Cuba.

Roswell had performed at Soundscape in the early 1980s and before that knew Gillis when he was her advisor in her ethnomusicological studies. He also took part here and there in her presentations, like the landmark Interpretations of Monk concert in 1981. After abrupt life changes for both Gillis and Rudd in the late 1990s, they reconnected and found the perfect partnership in life and music. The above description above of Verna Gillis’s world traveling also works as a prospectus for her efforts she envisioned with Roswell. Forever making new musical friends from around the world, Gillis spun several of these the threads into Roswell’s musical journeys to Mongolia, Mali, China, and Korea, and collaborations with musicians from Puerto Rico and Cuba. Each musical direction brought a with new cast of players, and new records, mostly on Sunnyside. The collective wit of Gillis and Rudd also forged a new publicity epithet to clarify his re-emergence: Roswell was the "Artist formerly known as Avant Garde".

And that was also part of the new latitude: The turn of the 21st century for Roswell meant constant activity on these new international efforts, and regular activity closer to home with Michael Doucet of Beausoleil, Puerto Rican cuatro player Yomo Toro, guitarist David Oquendo; strong new connections with guitarist Duck Baker and bassist Mark Dresser; and reunions with Henry Grimes, Giuseppi Logan, the New York Art Quartet. He also codified his years of study with/on Herbie Nichols into a definitive volume of manuscripts, The Unpublished Herbie Nichols.

Roswell’s 75th birthday in 2010 was celebrated with a New York City concert at City Winery, including an international cast of talents from among Roswell’s contemporaries and succeeding generations. November birthday tributes followed over the coming years, including the commemoration of his last one—with Rudd in attendance, though not playing.

The seventh and final decade of Roswell’s performing career was full of the vibrancy and power of the previous ones, though with a slightly lower amplitude. He was based in Kerhonkson, New York, and getting the most out of the impressive talent pool in the Hudson Valley. Appearances in New York at Dizzy’s, Joe’s Pub, Le Poisson Rouge, and Symphony Space showcased the projects that had been piloted and rehearsed in Ulster County, and often recorded in Rhinebeck: The trio with Heather Masse and Ralf Sturm; quartet including Ken Filiano, Lafayette Harris and Fay Victor; the versatile John Medeski playing many roles, ongoing work with Beausoleil and Steven Bernstein’s Sex Mob.

Roswell continued to testify: For Archie Shepp’s induction as a Kennedy Center honoree, as guest on Prairie Home Companion, and as an essential living connection for researchers and musicians to Herbie Nichols, Albert Ayler, now to Steve Lacy, Alan Lomax, and so many others. He took a first-person role in retrospective projects covering the New York Art Quartet, his once-obscure Blown Bone from 1976, and both recent and recently-discovered music in conjunction with Lacy. Meanwhile he continued to wow kids as elementary school guest artist, and was the linchpin in beginning musical studies for young friends and family in the area. While he continued performing, Rudd was slowly treating prostate cancer through his last five years; if anything the diagnosis sharpened his sense of the value of time spent on what mattered.

And it was an opportunity to reflect. Through the decades Rudd had written hundreds of pieces of his own, and had a unique angle on maybe ten thousand more items from the general musical literature. A Roswell Rudd songbook project was prepared (Keep Your Heart Right), and another gathering off-beat choices of "standards" (Trombone for Lovers). He also sat down to document his life history in his own words, an essential body of thought for the ongoing study.

We are still studying those words and will continue to; there’s much to savor. Roswell ultimately was a gentle man operating in bombastic musical and social spheres where the din may have kept us from listening closely enough to the truth he had to offer. That sharpness is well exhibited in his legacy of copious recordings, detailed musical notation, thoughtful letters and personal ruminations that are now being shared through the Jazz History Database.